Throughout the summer, we are posting photos from places where the CLST students travel, do research, excavate, and teach.

Here comes the final post for the summer of 2015. Many thanks to all contributors for impressive and beautiful photos, documenting a wide range of summer research and study!

The thirteenth winner is Evan Jewell, whose photos from Nîmes in France and from Greece we posted earlier this summer. After his travels, Evan was teaching a Latin class at Columbia. He wrote to say that the class was a great experience for him. He taught seven students with very different backgrounds, some of them from CLST and other programs, others already in their respective professions as teachers and academics in other fields, and several coming to CU’s summer session from other countries. And as he puts it, one of the great aspects of teaching during the summer at Columbia is that you can escape the classroom and make full use of the abundant ancient collections on show in its vast array of museums. Inscriptions are a great way for beginners to not only come face-to-face with an ancient artifact which preserves the language, but also gain a sense that this was really a “living language.” For example, the students encountered deviations from the “canonical” grammar and orthography that they had learn from their textbook. In addition to study at the Metropolitan Museum, the class made use of Columbia’s own very well appointed Olcott collection of ancient artefacts, housed in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library (RBML) at Butler Library. Photos and descriptions by Evan Jewell.

Evan’s Latin class meeting for an extra session on Latin epigraphy at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, by Evan Jewell. I had students from my own Intensive Beginners Latin course, as well as Intermediate Latin and Augustan Poetry come along–it proved to be a great Friday afternoon! Pictured here, some of the students ponder a set of inscriptions from the fascinating tomb of the Vibii in Rome (probably Flavian or Trajanic in date).

![One of the more unusual inscriptions that we examined at The Met is known as the "Vivas Diatretum", a 4th century CE glass beaker in a bronze cage, encircled by a bronze inscription in relief which reads: BIBE VIVAS I[ . . ]A[?] "Drink so that you may live (?)" (the last word is uncertain). It dovetailed well with the fact that my students had just learnt the subjunctive mood that week! By Evan Jewell.](/sites/default/files/cs-Evan_Jewell_Photo2.jpg)

One of the more unusual inscriptions that we examined at The Met is known as the “Vivas Diatretum”, a 4th century CE glass beaker in a bronze cage, encircled by a bronze inscription in relief which reads: BIBE VIVAS I[ . . ]A[?] “Drink so that you may live (?)” (the last word is uncertain). It dovetailed well with the fact that my students had just learnt the subjunctive mood that week! By Evan Jewell.

Students each chose two inscriptions and conducted an autopsy of their inscription, working up a rough edition and then translating their text. Besides providing fairly simple texts to read and a further introduction to Latin epigraphy, the session also presented an opportunity to tell my students more about the Roman social life and how these inscriptions commemorated not only the dead, but advertised sometimes complex social relationships and dependencies, such as slaves commemorating their fellow slaves (“conservi”), a father commemorating his foster-son (“alumnus”), or some students (“discentes”) commemorating their teacher. By Evan Jewell.

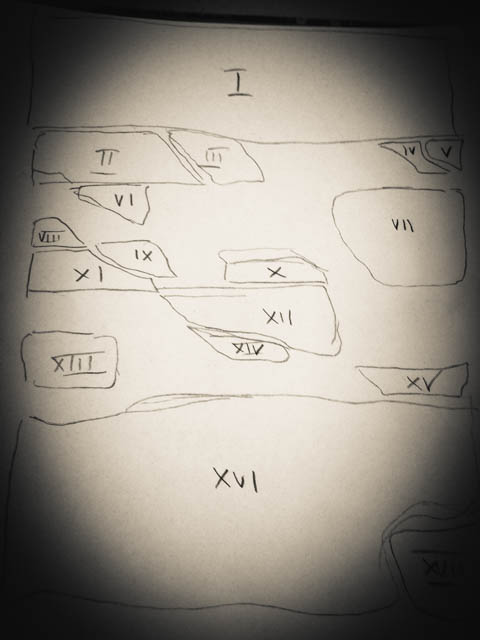

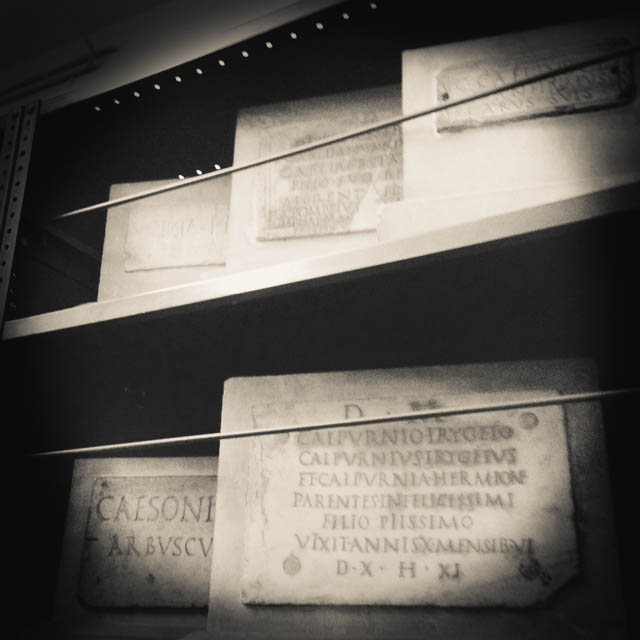

The twelfth winner is incoming student Stephanie Melvin, who was attending a summer school organised by the British Epigraphy Society and the British Museum before moving to New York and Columbia campus in August. Attendees had the chance to explore the British Museum’s extensive epigraphic collection, most of which is, regrettably, stored underground and out of sight. Tasks included sketching, transposing and deciphering epigraphic texts with a final view to producing an edition to be published on the British Museum’s online database. Photos and descriptions by Stephanie Melvin.

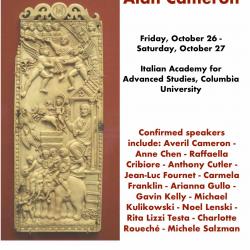

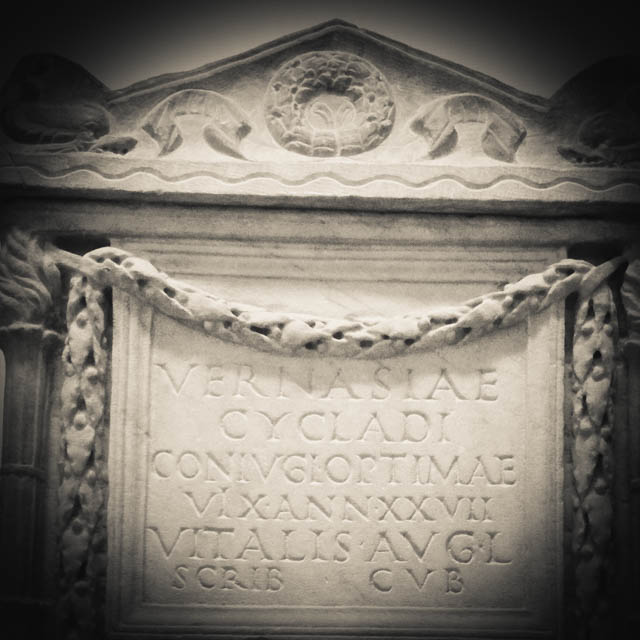

Grave-marker from the British Museum’s collection, by Stephanie Melvin. This beautiful grave-marker from the 1st century BCE is dedicated by a former slave of the Emperor to his wife Vernasia Cyclas.

A sketch of the stone, now in various fragments, on which my inscription was found in the temple of Athena Polias in Priene, by Stephanie Melvin. This kind of sketch is the first stage when approaching a new find. The first block is Alexander the Great’s dedication, while the rest is a letter from Alexander detailing the rights and privileges of the city and its territory.

A glimpse inside the great storeroom, by Stephanie Melvin. The storeroom contains thousands of funerary inscriptions, most of which come from columbaria and were collected by the upper classes during their ‘Grand Tour’ in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The eleventh winner of the CLST Photo Award is incoming PhD student Deborah Sokolowski. Deborah moved to the city and to the Columbia neighborhood already for the summer term (welcome!). She sent us photos from campus and Riverside Park in the sun, and from the German class she took with Johanna Urzedowski, PhD student in Columbia’s Department of Germanic Languages. Deborah writes that one of her favorite parts about walking through campus is its hidden treasures, like a bronze sculpture of Pan, originally commissioned for the upscale Dakota apartment building on the Upper West Side (where John Lennon lived). Photos and descriptions by Deborah Sokolowski.

The Great God Pan (George Grey Barnard, 1863-1938) with Butler Library in the background, by Deborah Sokolowski. The sculpture was donated to the city of New York with the stipulation that it be featured in Central Park. The Board of Parks refused the gift, and it remained in storage for some ten years before eventually finding its home on Columbia’s campus in 1907. I especially like the lion-headed spigots on the base of the sculpture, reminiscent of Barnard’s original intention for Pan as a fountain.

Taking a class in Columbia’s summer session, by Deborah Sokolowski. I spent the majority of my summer taking a course at Columbia, “German for Reading Knowledge,” to prepare for her modern language requirement. The course, instructed by Johanna Urzedowski, developed strategies for translating scholarship in students’ respective departments.

Just a few blocks from campus, Riverside Park is a quiet escape from the city bustle with its winding running trails and tall trees, by Deborah Sokolowski.

The tenth winner of the CLST Photo Award is Jeremy Simmons. After excavating at Hadrian’s Villa for a second time, he visited some of the ancient sites of the Bay of Naples. While at Pompeii, Jeremy writes, he was particularly struck by some of the incredible wall paintings that survived in various residences throughout the site. Excavating gave him an entirely new appreciation for this medium. Photos and descriptions by Jeremy Simmons.

Border decoration in the Villa of the Mysteries at Pompeii (dating to around the first century BCE) that exhibits various techniques simultaneous, including geometric patterning, vegetal motifs, and the imitation of marble, by Jeremy Simmons. I find it really interesting that such an elaborate border surrounds one of the most iconic wall paintings from antiquity, the eponymous scenes of initiation rites into a mystery cult.

Detail from the House of Marcus Lucretius Fronto (first century CE), by Jeremy Simmons. This was one of my favorite houses in Pompeii proper. The faces take on almost a grotesque appearance due to their abstracted features (and the damage to the paint over time).

Detail from the House of Marcus Lucretius Fronto (first century CE), by Jeremy Simmons. I found particular beauty in the minute details of the decoration, such as the exceedingly precise architectural paintings.

Detail from the House of Marcus Lucretius Fronto (first century CE), by Jeremy Simmons. The use of various colored backgrounds is also striking, such as the small cupid on a field of yellow.

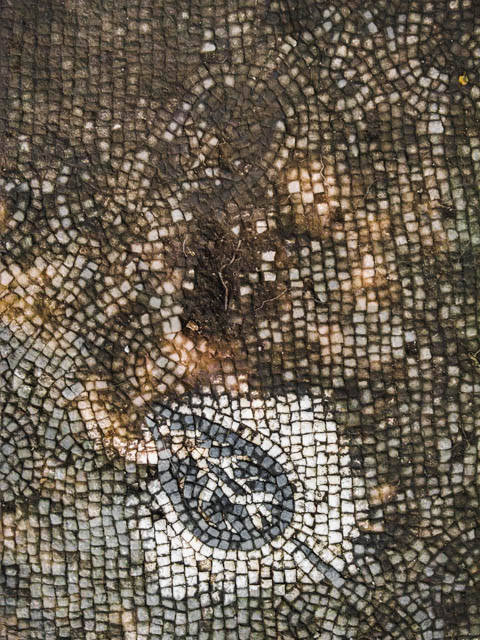

The ninth winner of the CLST Photo Award is Joe Sheppard, who is again excavating at Villa Adriana, in a project led by Professors Francesco de Angelis and Marco Maiuro. Joe sent us photos on a theme that is immediately relevant to the excavation: conservation. The photos document major findings, of walls, floors, mosaics, and more.

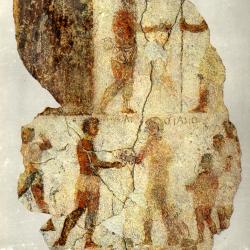

As Joe writes, sometimes the walls are not where you expect them: many frescoes in museums today have been painstakingly reassembled from countless fragments near the find spot. On the other hand, plenty of fragments of painted plaster, mixed in among rubble fills, are too faded or small to provide us with much information. The best way to preserve something buried for centuries is not to unearth it in the first place. It hampers excavation, however, having to leave delicate wall paintings covered behind a thin column of dirt, which is a temporary solution at best. In between the thrilling discovery of excavation and the analysis of material culture on-site and in museums–two experiences many of us have enjoyed–lies the crucial task of cleaning and preserving delicate archeological finds. This year at the Villa Adriana we learned how to take care of the fragile frescoes and mosaics that we unearthed, and learned more about the decoration of the villa in the process. Photos and descriptions by Joe Sheppard.

The decorative pattern of a black and white mosaic becomes clear only upon cleaning away the dirt that covered it for centuries. Although the many tesserae or small mosaic stones we find commonly scattered throughout various soil deposits attest to the fragility of this type of decorative floor surface, their durability can provide an immediate impact and direct connection with antiquity where they have survived in situ. By Joe Sheppard.

This image captures the moment just after two excavators realized they were coming down upon a large sequence of contiguous pieces from the same fresco, face up — an improbable find, given that they must have adorned a wall or ceiling originally. Only by excavating and documenting the plaster very carefully can the original decorative context be pieced back together. By Joe Sheppard.

Fragile stretches of cracked plaster, once cleaned and documented, can be held together with thin gauze strips, not unlike something you might see in a hospital. This method allows excavators to continue removing these soil “pedestals” and unearthing the remainder of the room, without destroying the highly fragile plaster decorating the walls. By Joe Sheppard.

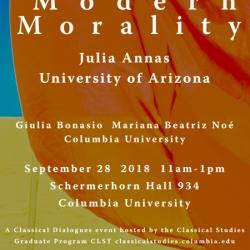

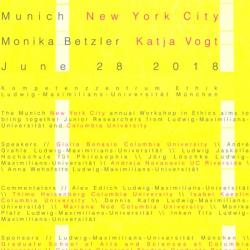

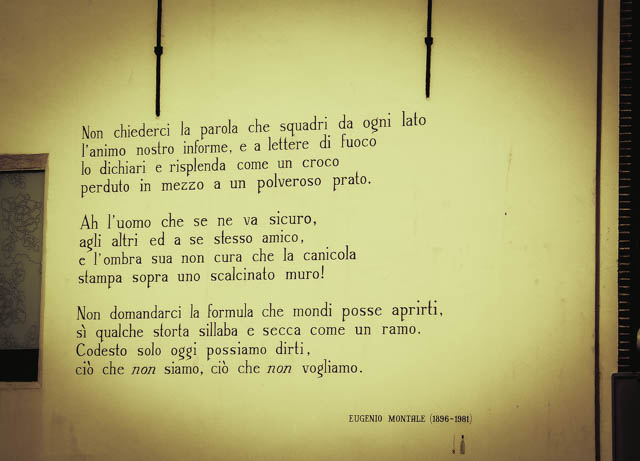

The eighth winner of the CLST Photo Award is Giulia Bonasio. Giulia spends the summer in Leiden, doing research for her dissertation on Aristotle’s Eudemian Ethics. While she works on happiness, virtue, and pleasure in ancient ethics, she also explores the “Wall Poems” project in Leiden. Photos and descriptions by Giulia Bonasio.

One of the main university buildings in Leiden, by Giulia Bonasio. In Leiden the buildings of the university are not confined in a campus but, since the university dates back to 1575, they are spread all over the city. The result is a mixture of old buildings and new architectures scattered among other buildings, some of them facing the canals and surrounded by parks.

A poem by the Italian poet Eugenio Montale written on the facade of a private house, by Giulia Bonasio. Leiden is beautifully decorated with poems in many different languages that you may discover unexpectedly at every corner. The project is call “Wall Poems.” It started in 1992 and by now counts 101 poems. I was lucky enough to find by chance one of my favorite Italian poems.

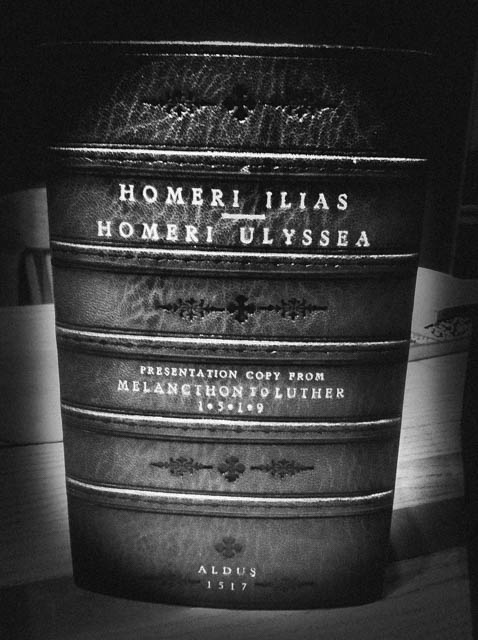

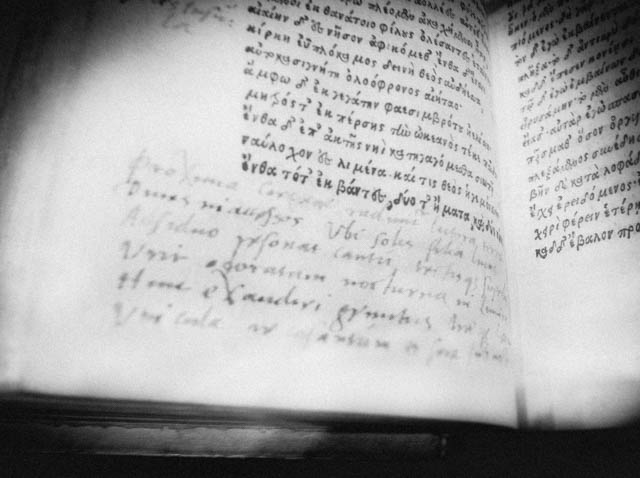

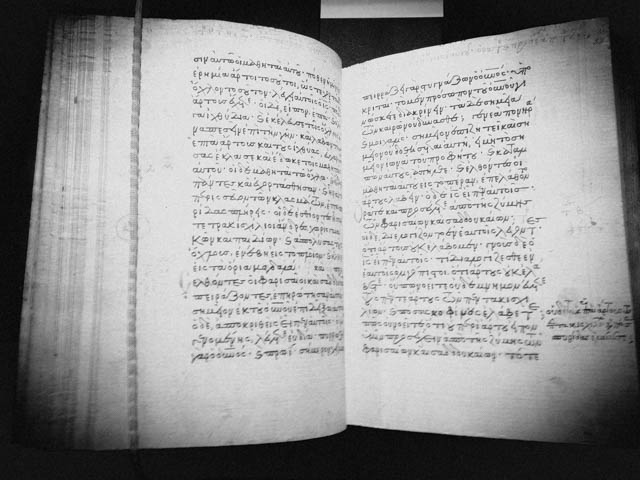

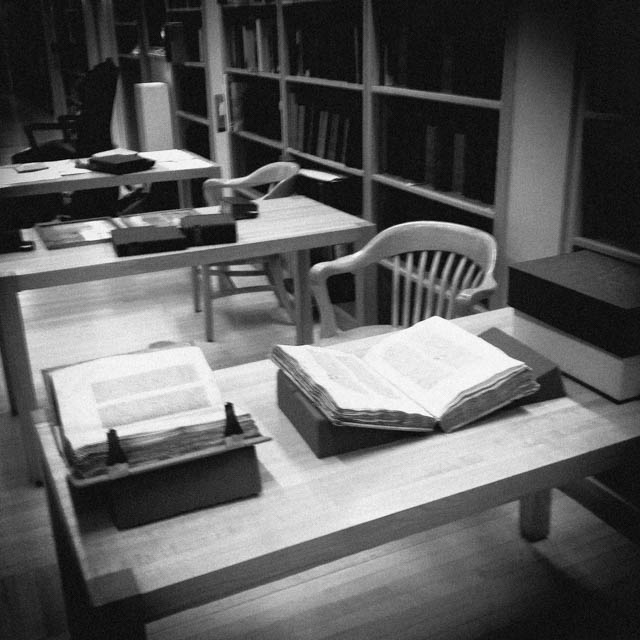

The seventh winner of the CLST Photo Award is Nicholas Lamb. Nick spends the summer working on his MA thesis as well as conducting research with Columbia faculty and curators on a number of the rare books in the Columbia special collections. He is making ample use of the special collections at the Columbia Rare Book and Manuscript Library and at Union’s Burke Library, and sent us photos of the two books he finds most fascinating: a 1517 Aldus edition of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and a manuscript of the Holy Gospels, produced between 1340 and 1360. Photos and descriptions by Nicholas Lamb.

Spine of a 1517 Aldus edition of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, by Nicholas Lamb. The book was presented to Martin Luther (1483-1546) by his friend and fellow reformer, Philipp Melanchthon (1497-1560).

Aldus edition of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey from 1517, presented to Luther by Melanchthon, by Nicholas Lamb. Melanchthon’s notes can be found in the book’s margins. From the Columbia Rare Book and Manuscript Library collection.

A manuscript of the Holy Gospels, produced between 1340 and 1360, by Nicholas Lamb. This manuscript appears to have been written in Italy but later may have come into the possession of library of Iveron Monastery on Mount Athos. This volume’s history is reflective of the close ties that developed between the Italian city-states and Byzantium during the Late Empire. From the Burke Library special collections.

The Reading Room in the Columbia Rare Book and Manuscript Library, replete with items from the special collections out on the study desks, by Nicholas Lamb. Columbia students are encouraged to make use of the special collections in the course of their study, and both my professors and Columbia’s curators have encouraged me to incorporate special collections work into my research.

The sixth winner of the CLST Photo Award is Douglas Wong. Doug participated in the CLST Global Class and excavation project at Villa Adriana in Italy, directed by Professors Francesco de Angelis and Marco Maiuro. He sent us photos from a Saturday excursion to the nearby Villa d’Este in Tivoli, where Professor John Pinto (Princeton University) joined the group for a tour.

One of the many fountains that comprise the garden in the Villa d’Este, Tivoli, by Douglas Wong. Built for Cardinal Ippolito d’Este, grandson of Pope Alexander VI, it is an impressive estate whose design was heavily inspired by Hadrian’s Villa (and it used remains as building materials as well!).

One of the columns found in the villa’s garden, by Douglas Wong. The design is that of the Apples of the Hesperides, one of the many images associated with Hercules; Cardinal Ippolito d’Este “traced” his lineage back to Hercules and thus used much of his mythos as imagery around the villa.

Another example of the extent and detail of the fountains in the villa’s garden, by Douglas Wong. All the water comes directly from the Aniene River, around a kilometer away, and this hydraulic system too was inspired by Hadrian’s Villa. The fountains and garden architecture were created by the papal architect Pirro Ligorio, who himself had excavated Hadrian’s Villa in 1549.

The fifth winner of the CLST Photo Award is Evan Jewell. Evan will be teaching Latin in Columbia’s Summer Session. Prior to that, he is traveling in Greece and France. The first photo comes from the Greek island Delos. Visiting this island over two days, Evan says, was the highlight of the Center for the Ancient Mediterranean’s (CAM) trip to Greece this May. The second photo comes from Nîmes in France, where Evan was doing research for his PhD dissertation.

The Maison Carrée, Nîmes, France, by Evan Jewell. The Maison Carrée was the main reason why I visited Nîmes and will form one aspect of my dissertation research on youth and power in the Roman empire. It has long been held to be an Augustan temple, possibly built around 16 BCE and then rededicated to Augustus’ grandsons, Gaius and Lucius Caesar, the “princes of the youth” (principes iuventutis) somewhere between 2-5 CE, on the basis of a reconstructed inscription. However, recent scholarship has questioned this dating, placing its construction in the Hadrianic period. In any case, the temple is one of the best preserved examples from the Roman world, due to its conversion into a church. One truly gains a sense of the imposing nature of its architecture and its experiential effect upon the viewer as they ascend the steep steps to the portico and cella.

The fourth winner of the CLST Summer Photo Award is Alice Sharpless. Alice is participating in the CLST Global Class and APAHA excavation at Villa Adriana, co-directed by Francesco de Angelis and Marco Maiuro. She sent us a series of images of sculpted faces in the Capitoline Museums in Rome. With these pictures, Alice tells us, she wanted to capture the emotions that can be expressed through virtuosic sculpting of faces, both animal and human. Photos and descriptions by Alice Sharpless.

A republican bronze portrait which has been identified as Junius Brutus since the Renaissance, by Alice Sharpless. The head was probably originally part of a full statue, and not a bust as it is seen today.

Detail of a lion attacking an antelope on a marble sarcophagus in the Capitoline Museums from the late 3rd c. CE., by Alice Sharpless.

Detail of the elder of a pair of centaurs from Hadrian’s Villa, signed by Aristeias and Papias of Aphrodisias, by Alice Sharpless. The two centaur sculptures originally included Cupid riders and represented the pain and pleasure caused by love.

The third winner of the CLST Summer Photo Award is Grant Dowling. Grant sent us photos from midtown Manhattan, where he is taking a summer Latin class at the CUNY Graduate Center. Class runs from 9:30am-4pm 5 days a week with optional early morning, lunch time, and weekend review sessions—all of it in the midst of New York City. Photos and descriptions by Grant Dowling.

The flag-lined entrance to the CUNY Graduate center, by Grant Dowling. The building used to house the “B. Altman and Company” Department Store from 1906 to 1989. Unlike Columbia, the second you exit CUNY’s classrooms you step right onto New York’s busy sidewalks.

Street view with CUNY Graduate Center, by Grant Dowling. The architecture of the building has lots of detail. Notice the ornate fluting on these columns. The Classics Department is located on the 3rd Floor of the Graduate Center. And the Empire State Building looms less than a block away!

Side entrance onto 34th Street, by Grant Dowling. The students usually use this door to go get lunch. After grabbing a meal from one of the many cuisines near by (or packing a lunch from home), the students often congregate in the 8th floor cafeteria to chat and study.

The second winner of the CLST Summer Photo Award 2015 is Evan Jewell, who is currently traveling in Greece. His theme for the below photos is materiality, inspired by the many differing uses of local and imported stones in the sites he has been visiting. Photos and descriptions by Evan Jewell.

Mycenae, the roof of the so-called tholos Tomb of Clytemnestra, by Evan Jewell. One of the few tombs of this type not to have had its ceiling collapse, the incredible ashlar blocks carved from a conglomerate rock allowed the builders of this tomb, and the so-called Treasury of Atreus, to achieve architectural feats of load-bearing engineering.

Eleusis, the “telesterion” or so-called initiation hall, which would have held a large number of initiates during the initiation rites, by Evan Jewell. Note how the seating is carved from the distinctive bedrock of the site, a feature I encountered at several other sites, from the Parthenon to the limestone fountain of Glauke at Corinth.

Detail from the Erectheion on the Athenian acropolis, Athens, Greece, by Evan Jewell. Here I was fascinated by the deterioration of the pentelic marble in the corner of this famous building–its almost crumpled-at-the-seams state.

The first winner of the CLST Summer Photo Award 2015 is Maria Dimitropoulos, who just graduated from the the Classical Studies MA Program and has been accepted into our PhD Program. Maria is currently traveling in the south of Italy. She participates in the Apulia-Paestum in Residence Archaeological Scholars Program, a seminar organized by the Newington-Cropsey Foundation. The program takes graduate students to the archaeological sites of Magna Graecia in South Italy. Impressed by the variety of sites, Maria sent us several images. Photos and descriptions Maria Dimitropoulos.

Temple of Athena in Paestum in the evening, 500 B.C, by Maria Dimitropoulos. This building is an early example of the Doric and Ionic architectural styles co-existing: it is a Doric temple yet there are Ionic columns.

Court in the House of Neptune and Amphitrite in Herculaneum, 1st century A.D. with a mosaic of Neptune and Amphitrite on the east wall, surrounded by frescoes depicting plants and fountains; by Maria Dimitropoulos.

Marble bas-relief decorating the front of the stibadium in the cenatio of the Villa Faragola in Ascoli Satriano, 5th – 6th century A.D., by Maria Dimitropoulos. The small marble slab depicts a dancer in front of an altar surrounded by a snake.